Throughout my time as a therapist, I’ve had one main objection against therapy. It’s an objection that can best be understood – and potentially solved – through the lens of friendship and witnessing.

Have you ever lost a friend because your ideas of friendship diverged? Sometimes it’s as simple as that. You lose a friend because your conceptualisations of friendship aren’t compatible.

This is how I understand a friendship: Two people voluntarily spending time together, and sharing a space together, without having too many requirements for that space. A friendship is two people who want to witness each other.

But other people might want something different from a friendship. They might want the friendship to result in something – a product or a work of art. Perhaps they need their friendships to be of some sort of use.

Knowing how deeply supportive, healing, and beautiful a friendship can be when a friend sees you, understands you and holds you in high esteem, but then also experiencing how uncomfortable it can feel to have a friend who seems to want something specific out of the relationship, has made me wonder why there isn’t more research within the psychological field of friendships.

It’s not that friendship is an underexposed topic in general, though, especially not if you turn to the realm of philosophy.

A Friendship Of Utility, Pleasure, Or Virtue

Probably most significantly, there’s Aristotle, the philosophy of friendship’s first-mover. In one of his most popular works Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle discusses a variety of subjects in order to find virtue and moral character, and one of these subjects is friendship. He categorises friendships into three types, depending on what the foundation of the friendship consists of: utility, pleasure, or virtue.

He explained that the utility and the pleasure friendships are characterised always by a degree of uncertainty, because the motivation for being in these relationships are based only on the extent to which they fulfil our needs. They are built on the underlying contract that they must give both parties reciprocal profit by means of utility and happiness, and thus they are also characterised by an inherent risk of disappointment and clash – which is what you might have experienced if you have ever felt that you no longer were of any “use” to a friend.

But then there’s the third kind of friendship: The good friendship, which is built on a more stable foundation than the other two, because the good friends prioritise the friendship, also when other considerations get in the way of the utility and the pleasure. Also, the wish for a good life seems to be most defining of the good friendship, which according to Aristotle is the life, where one is able to develop the most virtuous and humane sides. A person, he says, can only develop in relation to others, and more than anything else are we able to develop as human beings in the good friendship, where the boundaries between what is mine and what is yours vanish and the relationship turns into selfless love. It was a distinctive feature of Ancient philosophy that relationships were a given in individual happiness.

Now if we fast-forward to today, our conditions are pretty much as different as can be from those existing in 350 BC, but surprisingly the friendship figures that contemporary philosophers point to in today’s arena are quite similar to Aristotles friendship types.

In fact, in his book Friendship in a Time of Economics, the American political philosopher, Todd May, identifies two figures, which can be seen as contemporary and economic versions of Aristotles’ pleasure and utility friendships: He calls them the consumer and the self-entrepreneur.

The consumer relationships are those that we participate in for the pleasure that they bring us. The entrepreneurial relationships are those that we invest in, hoping they will bring us some return. And his point is that these two types of relationships reflect the lives that we are encouraged to lead by the neoliberal discourses.

And this leads us back to the common type of friendship clash, where the relationship caves under the pressure of a dominant economic discourse, when questions like “what is this worth, am I having fun, what do I gain from this?” begins to dominate. And if these are the primary questions being asked, my belief is that the friendship takes on an economic character that in fact isolates people more than it connects them.

But like Foucault says, “where there is power, there is resistance”, and in this light, what Aristotle called the virtuous friendship, and what Todd May calls the true friendship, can stand as a challenge to the tenor of our times.

This third kind of friendship is the non-economic one, and it’s the one that allows us to see ourselves from the perspective of another. It’s the one that can open up new interests or deepen current ones, and maybe most importantly, it’s this kind of friendship that supports us during difficult periods in our lives. Shared experience, not just common amusement or advancement, is the ground of the deep friendship.

True friendships rely neither on diversion or return but on meaning. They expose our vulnerabilities and add dimensions of significance to our lives that can only arise from being, in each case, friends with this or that particular person.

Like the French nobleman and father of the essay, Michael de Montaigne (1533-1592) said about his friendship to Étienne de la Boétie: “If you press me to say why I loved him, I can say no more than because he was he, and I was I.”

So if a friendship can work as a motor of meaning and as support, even when we are neither fun, nor useful, isn’t it odd that it isn’t one of the most researched of all human practices within psychology and the social sciences?

And if friendships are the least institutionalised and thus the most voluntary human relationships out there, based on reciprocal sympathy and support – things that are known to have a positive effect on the individual’s wellbeing – then why aren’t practitioners more focused on friendships in their therapy work?

The Friendless Therapeutic Set-Up

It’s commonly understood that unless a problem is directly shown and manifested in a relationship, it is only normal to go therapy alone – you don’t just bring along a friend!

The set-up across the different schools of therapy is rather that clients enter a context secluded from the concrete external conditions that make up their everyday life to “look inward. Here, in the therapy room, you’re supposed to work on yourself for about an hour. What this also means is that it’s mostly up to yourself to try and incorporate the potential insights and self-work that you’ve made into your everyday life.

Whether the therapeutic modality is cognitive and “tool-based” or psychoanalytic and depth-oriented, the set-up shares a set of concrete realities: Originally, it entails one therapist who’ll hold a certain kind of expert knowledge, and one client with a more or less specific problem, that they want help with. These two people are placed on each of their seats, often with a table in between them. And on the table there is very likely a pack of Kleenex.

The problem is that when the session is over, then a used Kleenex might be the only concrete artefact that the client takes away from the conversation. When clients leave the room, they so to speak leave behind the “togetherness” that has been established with the therapist. Whether the insights that the “togetherness” resulted in will be implemented in the client’s daily life is entirely up to the client in most therapeutic set-ups.

But what if therapists start making it their priority not to reproduce the notion that it is the individual’s sole responsibility to make best possible use of the therapy? What if the therapist instead strives to counteract the all-encompassing Western ideal of individual self-responsibility and self-improvement? Is this even possible?

When I searched the landscape for alternative therapeutic set-ups with a bigger focus on the way our identities and problems are socially constructed, I came across what is known as “definitional ceremonies” or “outsider witnessing practices”.

It has been practiced and made popular by the Australian social worker and psychotherapist Michael White, who in his work often would invite witnesses into the therapy room to help the clients reclaim or redefine their identity.

Long story short, the witnesses, who often were recruited from the therapist’s index of earlier clients, are asked in different ways about what it means to them to have witnessed the therapeutic conversation and what it resonates with in them. The point is that the witnesses’ retelling will strengthen or “thicken” the client’s preferred narratives, by giving them a more social character.

Definitional Ceremonies

This kind of social “identity work” that lies within the definitional ceremonies and remains ever relevant to friendship and therapy, was actually first described by the American anthropologist Barbara Myerhoff in 1976, when she participated in a research project about social contexts for aging, and hereby came across a recurring theme: elders’ invisibility in our society.

In Venice, California, she met a group of older Jewish immigrants, who had lost their families to the Holocaust and therefore felt isolated and invisible – feelings that manifested in depression and physical debilitation. What she experienced was that these people were really eager to present themselves, to be noticed, and to communicate their stories to a broader world. More than anything, they longed for an audience, because without being witnessed, they would be forgotten – as would their culture. Therefore they did all what they could to gather witnesses, and Myerhoff decided to support these efforts.

She would participate in the creation of small spaces, where the older citizens could reclaim their raison d’etre by witnessing and retelling each other’s life stories. In this community, the elders had the possibility of being visible on their own terms, “the old Jews (…) managed to convey their statement to outsiders, to witnesses who then amplified and accredited their claims”. It was these spaces that she called definitional ceremonies, and it was these spaces that she found contained the power to reduce the isolating and individualizing effects that different contemporary societal structures and discourses and hereby problems can have on people.

Especially the narrative (and systemic) therapies, with the aforementioned Michael White as a front figure, have made witnessing a central part of the therapeutic set-up. Outsider witnesses are invited into the session to resonate with the client’s story in a non-judgmental and curious way – to engage with the story without prejudices, so that the clients’ preferred narratives are affirmed on their own terms, and the clients hereby are empowered to develop their own expertise and have their agency strengthened.

This kind of ceremonial practice tries to counteract the traditional therapeutic set-up’s risk of unintentionally confirming the clients in being alone and isolated with their problems within the secluded therapeutic room. It assumes that our identities are socially constructed and thus, since one could argue that helpful therapy equals successful identity work, it tries to create a therapeutic set-up that is more social and inclusive.

But even though the identity work is explicitly social in the outsider witnessing practices, the question is still whether it’s abstraction from the client’s everyday life will result in the work not being properly translated to the client’s daily life.

Consider, for instance, that though the identity work might be going really well, and the clients might be feeling more empowered and in touch with their values, will this matter if the clients aren’t being supported in these changes by their surroundings? If the surroundings don’t back clients up and affirm them in these changes, the changes might not ever sediment into their daily life. This is my main worry.

Between friendships and witnessing

The friendship contains a potential of witnessing and support that only rarely is used within the therapeutic set-up. This is a shame. A therapy that doesn’t include the conditions and the relations that make up the client’s everyday life, undermines the significant impact that people and events outside of the therapeutic context has on the therapeutic outcome. And if the therapeutic work feels too abstracted from the client’s daily life, the client risks feeling isolated and alone in the process going on in between sessions, and might not even get anything out of therapy.

A way for the therapy to incorporate a link between the sessions and the daily life, would be to try and ensure that the insights of the session are being accepted and supported by the people that the clients newly appropriated narratives normally would be shared with. The inclusion of the friendship in the therapy would contribute to this kind of support.

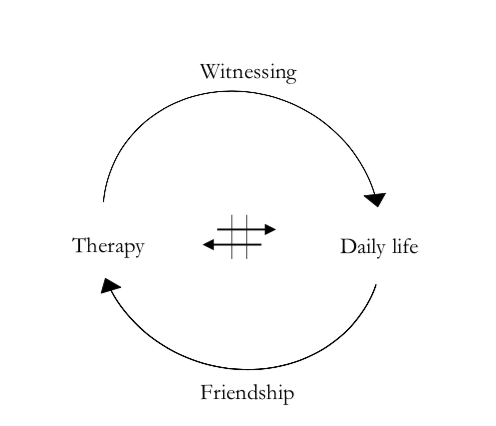

I’ve made a very simple model to illustrate the relationship between therapy and the client’s daily life, and I’ve tried to show with this model how witnessing and friendship place themselves in an interacting relationship. I’ve demonstrated the seclusion of the therapy from the client’s daily life with two vertical lines – and the therapy’s impact on the daily life as well as the daily life’s impact on the therapy is visualized with the two arrows going in opposite directions.

What I’ve tried to conceptualize with this model is what might happen if a client was offered the possibility of bringing in a good friend to affirm them in their identity work. As a witness, the friend could act as a supportive link between the therapy room and the client’s remaining life. Hereby the witnessing friend could help ensure that the insights made in session are translated to the client’s everyday life.

So let’s go back to the therapeutic set-up and then let’s try to add a chair. Because today the client has decided to bring a friend . It’s not because the client’s problem lies within the friendship – that’s not why the friend has joined. On the contrary, the friendship, with its inherent witnessing potential and its ability to counter the individualizing structures of our times, could become part of the client’s solution.

Further Reading

Friendship, Intimacy, and the Contradictions of Therapy Culture https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/17499755231157440